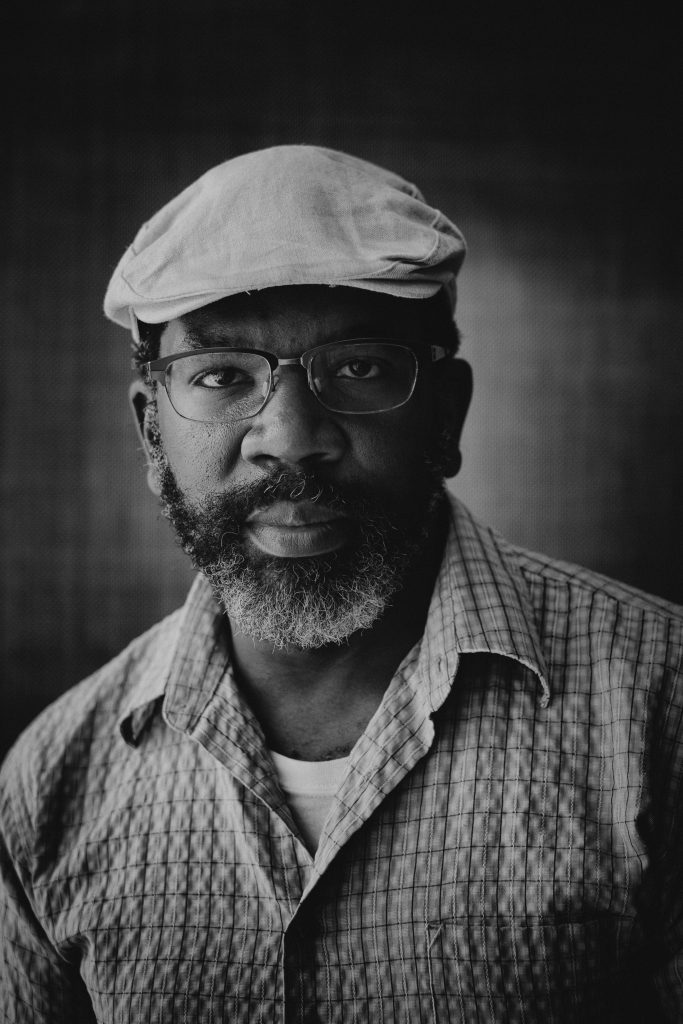

RICHMOND, Va. – Paul Rucker doesn’t shy away from the controversy surrounding his KKK-themed art exhibit. In fact, he hopes his work will spark a national conversation on institutional racism.

Some of the most striking pieces of the exhibit, called “Storm in the Time of Shelter,” are now on display in Richmond, Virginia, and include hand-sewn Klan robes, created from all types of materials and patterns, which range from vivid African Tribal print to pink camo.

“My show is really not about the Klan,” Rucker said. “My images are not about the Klan. They’re about the policies the Klan wanted in place.”

The exhibit calls out institutional racism by displaying original works of art which show how KKK policies are ingrained in American society today, said Rucker, a historian, musician, public speaker and artist from Baltimore.

The exhibit, which opened on April 21 at Richmond’s Institute for Contemporary Art, is not without its controversies. After successfully showing the exhibit in six cities without issue, Rucker’s show sparked debate last summer at York College in York, Pennsylvania.

His exhibit, then called “Rewind,” opened right before Labor Day, a few weeks after the Unite the Right rally turned violent in Charlottesville, Virginia. Five days after it opened, the York College administration decided to close “Rewind” to the public, and allow access only to students and community members with special invitations.

Rucker disagreed with the decision. He hoped that his work would be open to the public so the community could start an informed conversation, which he believes to be the key to social progress.

“It was a missed opportunity,” Rucker said. “York has a lot of history that they probably need to deal with, but they haven’t dealt with.”

York is known for its Civil War history. The town is located about 30 miles away from where the battle of Gettysburg was fought, according to the U.S. National Parks Service.

Matthew Clay-Robinson, director of York College Galleries who helped to organize the exhibit, said “the college trustees and administration felt blindsided by the exhibition and were concerned that it might stir trouble, opening three weeks after Charlottesville.”

Yet, despite the concern about the contents of the exhibit, Clay-Robinson said it was still mostly well received within the student community. He spoke about how “Rewind” drew the largest attendance of African-American students and community members the school had ever seen for one of their exhibits.

Todd Allen, a professor of communication at Messiah College, located in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, saw the exhibit several times and eventually met Rucker. For the last 17 years, Allen helped to lead a civil rights bus tour of the South, so the show was of particular interest to him.

“We talked about the robes and I remember sharing with him that since I teach this stuff as well, that I have a KKK robe in my collection,” Allen said. “I just talk about the impact. It’s one thing to talk about the hate groups in abstract but when you’re literally seeing and touching it, it has a certain kind of eeriness.”

In conversation, the two men, both of African-American descent, joked that Rucker’s art collection contains some of the most well-made KKK robes in the nation.

Both Rucker and Allen spoke about the importance of making more people aware of civil rights history.

To supplement his exhibits, Rucker also designed a 20-page newspaper, which is offered at the entrance of his shows. Inside is information on ways the KKK’s policies are still alive in the U.S. and historical context about civil rights.

“When we talk about facts we can have a productive conversation,” Rucker said. “When we have a productive conversation we can make progress.”

Besides the KKK robes, the exhibit also features other works that help to teach viewers about racism today. Rucker created a data visualization map that he shares during his public speaking engagements. It highlights Rucker’s finding that a new prison has been built in the U.S. every week since 1976. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, people from African-American descent are five times more likely to be incarcerated than people of Caucasian descent.

Other themes Rucker explores in his art are the racial divides of neighborhoods, environmental racism and the disparity of school funding.

“These policies created 100 years ago are still in place today and they’re not being supported by people in pointy hats,” Rucker said. “They’re being supported by normal everyday people who would probably never call themselves racist or think about racism being an intentional thing.”

Rucker’s work isn’t the only art involving the KKK sparking national controversy. In Austin, Texas, the Blanton Museum of Art at the University of Texas is currently displaying a painted piece by Vincent Valdez, which explores the modern day representation of the KKK in American society. After receiving feedback from students, faculty and staff at the University of Texas, administration decided to open the exhibit on July 17. But the exhibit has a sign warning potential viewers about its content.

“Storm in the Time of Shelter” is on display in Richmond until Sept. 9.