BETHLEHEM TOWNSHIP, Penn. — It started in 2010, when a black family found shards of glass in their yard, holes cut in the lining of their inflatable pool and a bag of sex toys on their children's trampoline.

Robert T. Kujawa, 45, had moved in next door earlier that summer. He hung Confederate flags from his windows, but only those facing the home of his black neighbors, Antonio and Biafra Baker. Kujawa called them the N-word.

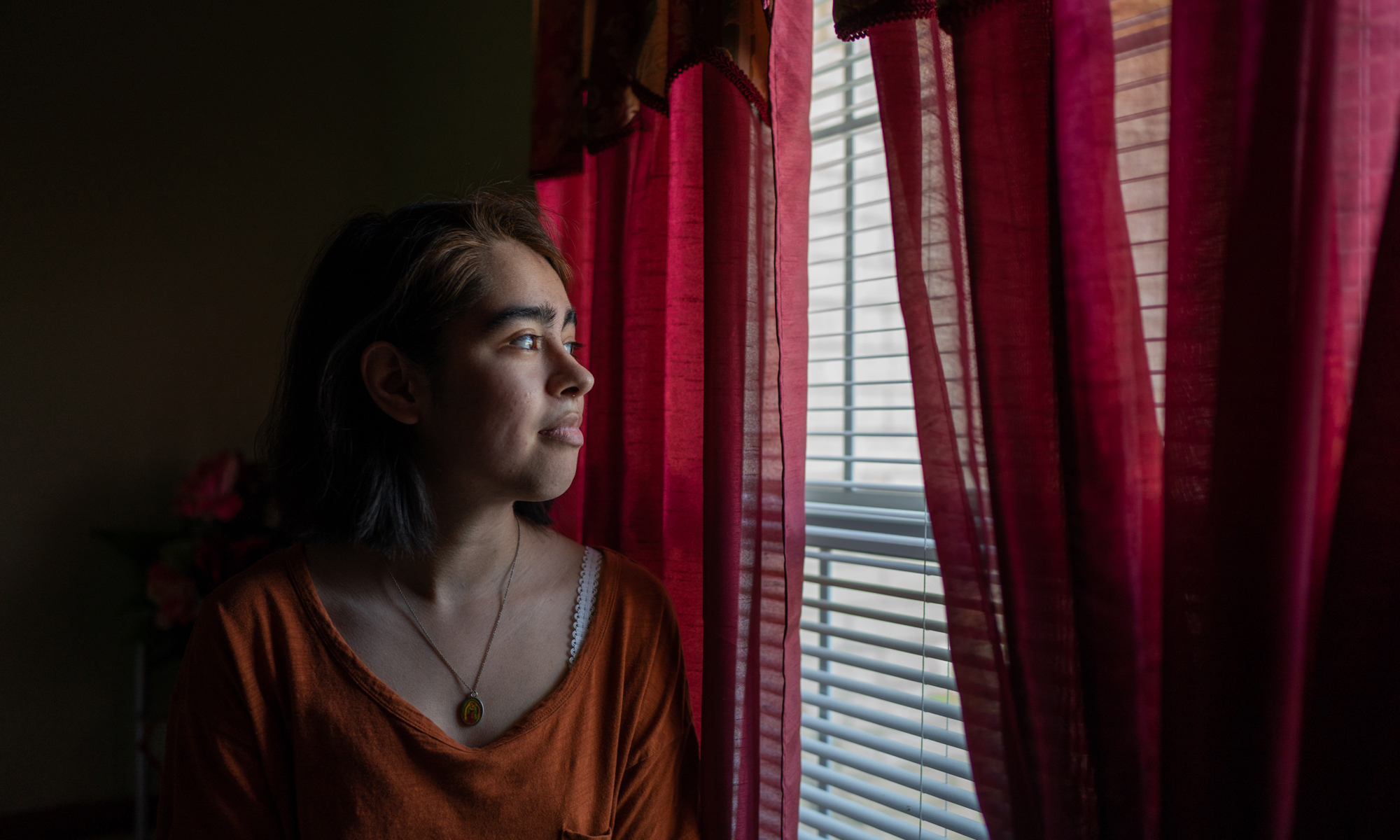

“The one thing that really broke my heart was the first time my boys asked, ‘Is he going to kill us?’” Biafra Baker recalled.

After seven years and at least two-dozen interactions with local law enforcement, Kujawa was arrested, tried and convicted of two counts of committing ethnic intimidation, Pennsylvania’s equivalent of a hate crime charge.

The federal government and 45 states, including Pennsylvania, and the District of Columbia, have laws criminalizing bias-motivated crimes, or hate crimes. Arkansas, Indiana, Wyoming, Georgia and South Carolina do not.

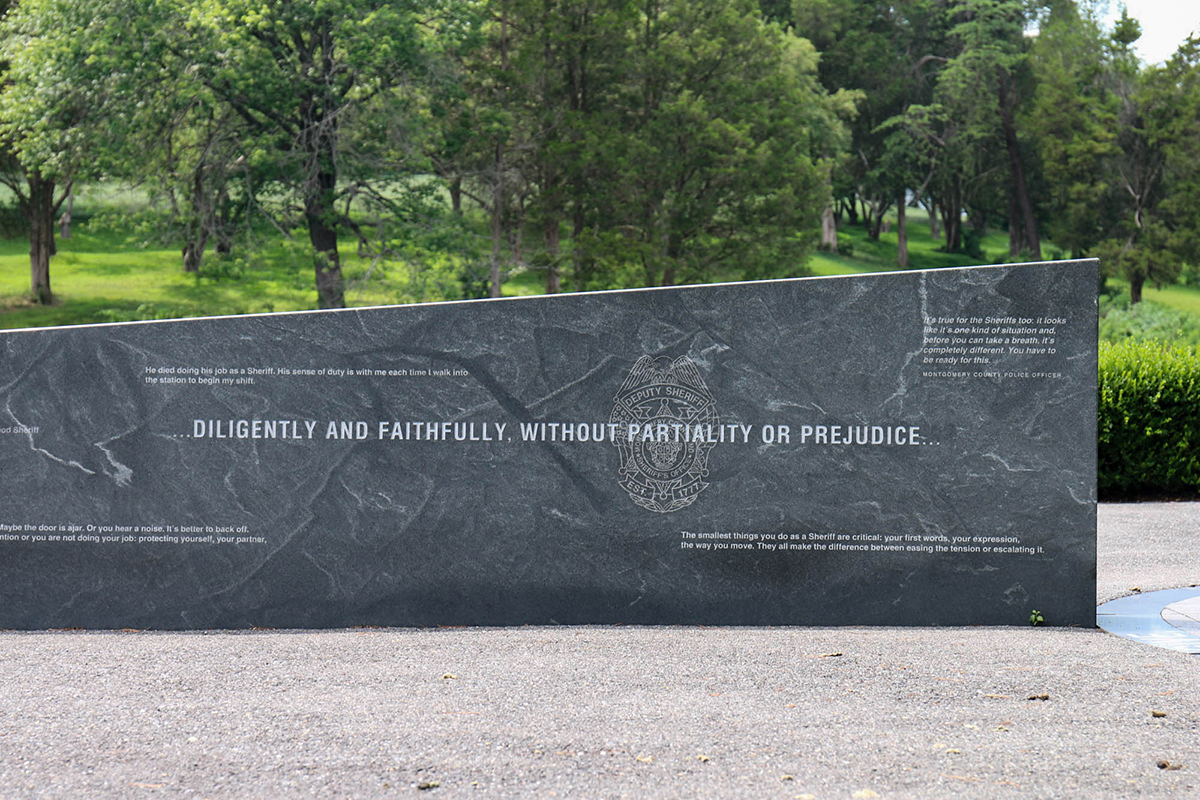

But how those laws are enforced largely depends on the law enforcement officer who responds to the call.

“The patrol officer is the most important official with regard to assessing hate crime because if done incorrectly at the entry level, it almost always doesn't get responded to in the appropriate manner,” said Brian Levin, a former New York Police Department officer who directs the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino.